NFC, Barcodes, QR Codes & Geolocation

When mobile payments are used in shops & cafes, in the real world

Your user is standing at the register in a grocery store. The cashier rings up her purchases, and a total amount displays on a screen. Your user has pulled out her phone with the intent to pay using your app. What happens next? This is, of course, the crux of mobile payment design, and if the experience is unclear or broken, or simply takes too long, you can bet the user will not give your app a second chance.

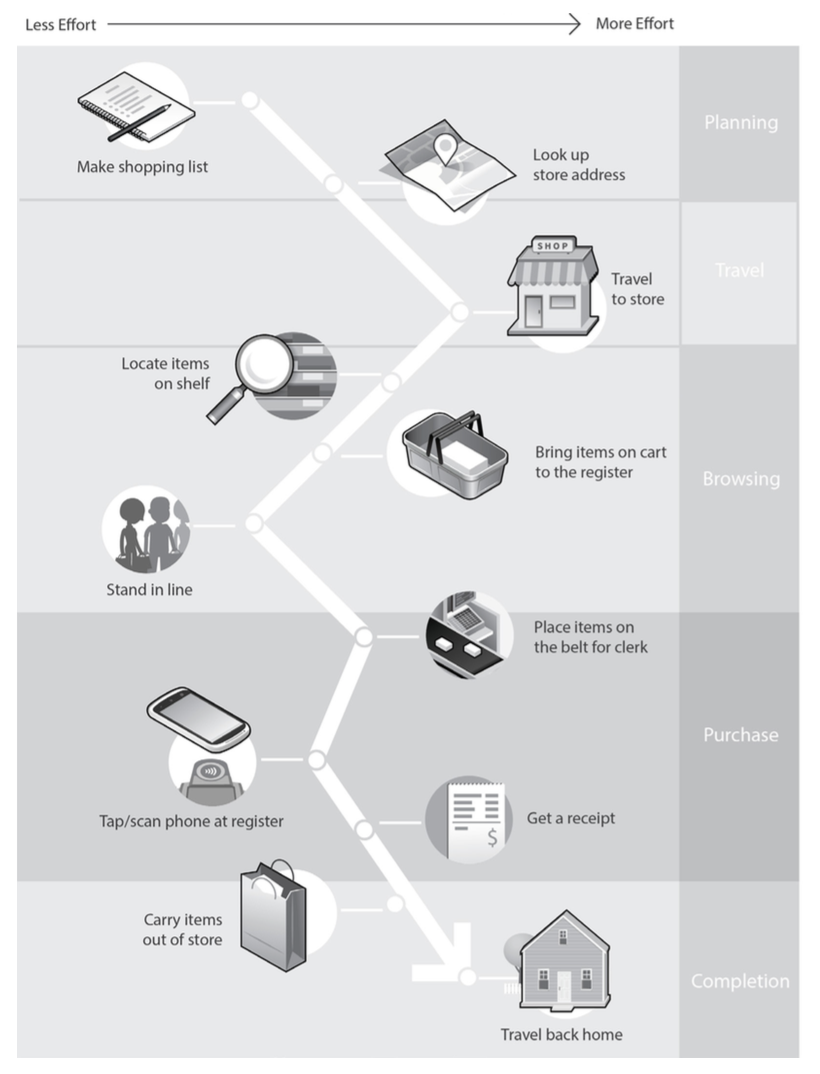

Regardless of the method you utilise, the most important factors to keep in mind when plotting out your payment flow are time and effort. In the context of a shopping experience, the window during which a payment at the register happens is relatively tiny, compared with all the effort users expend in the process of purchasing something. A task analysis of a typical shopping trip reveals five phases: planning, travel, browsing, purchase, and completion. Each phase has its own set of tasks that users must complete to reach their end goal — buying groceries, for example.

When designing your checkout experience, consider the cost of user effort with the timing of these tasks, in context with all the other steps users have to take to get to this point, and think about how those previous tasks might influence their mindset. Are they annoyed because they waited in a long line? Did they find everything they wrote down on their shopping list? How many bus transfers did they make in order to get to the grocery store? In terms of mental and physical effort, the payment experience should rank near the lower end of the scale, with the least amount of friction possible.

Mobile payments are not meant to be complex, engrossing, and experiential — like games or social interactions . They should be lightning quick and dead simple; otherwise, your app will just get in the way of your users enjoying or using whatever it is they set out to buy . It’s important to remember that interacting with your app is never the user’s end goal .

This chapter will focus on designing successful mobile interactions at the point of sale, using the three most popular payment methods: NFC, QR (quick response) codes and 2D barcodes, and geolocation . The table bellow shows the UX benefits and challenges of the three frame- works we will explore, and which live apps you can refer to as examples of the respective technologies in action.

Near Field Communication (NFC)

NFC presents a whole new mode for consumers to use their mobile devices, in which they can interact with their physical environment (tags, other NFC-enabled devices) instead of being passive “receivers of information” via their phones. NFC lets mobile users tap to initiate a short-range data transfer. NFC technology can be used to open a door, pay a transit fare, or swap contact details and pictures.

Apart from the novelty of bumping phones together, NFC offers many other advantages, like being built on well-established global security standards and simplifying the redemption of loyalty cards and coupons . The latter feature appeals especially to retail marketers that wish to drive up redemption rates of their promotional programs, and explains the recent buzz around large mobile operators and device manufacturers partnering with financial institutions to put a stake in the ground of mobile wallets. This model will only become more prevalent given the growing numbers of new NFC-enabled Android, Windows, and BlackBerry phones shipping—nearly 235 million in 2013.

Because NFC is largely dependent on hardware, and has a variety of usage patterns (authorise and tap, versus Tap & Go without opening the app), designers must create obvious feedback patterns for when the phone taps a reader, and the outcome of the payment. NFC payments also require more instructional cues than 2D barcode/QR code- or geolocation-based apps, as many users are not familiar with how NFC works. The last thing a user wants is to get to the register and fruitlessly bonk their phone on the point-of-sale with no apparent results, holding up the checkout line.

Barcodes and QR Codes

Apps like Starbucks, which use barcodes and QR codes, are fast becoming what I like to call the “gateway drug” of mobile payments . That is, consumers who have become comfortable with using 2D barcodes often find it easier to move on to NFC, geolocation, remote ordering, or other payment models. In the US, at least, Starbucks is the first real exposure that most consumers get to mobile payments, with over 10 million customers providing about 11% of the company’s revenue. Resembling a digital Rorschach image, QR codes can be encoded with data that will direct POS scanners to charge a registered account or a prepaid card. This method is generally faster to implement than NFC wallets, though it is less secure due to the exposure of the user’s payment source on screen in the form of a visual proxy. There are no encryption standards for barcode- or QR code–based wallets, so codes can be vulnerable to theft or interception. Still, with emerging concepts like tokenisation, barcodes and QR codes may have a shot at supplanting NFC as the most secure method of mobile payments. The major card companies like Visa and MasterCard have yet to issue specifications that endorse these methods per se, but it’s conceivable that they will, should tokenised 2D codes emerge as the frontrunner for the consumer market.

Point-of-sale experiences with this method typically require the user to either align his phone’s screen with a POS scanner (held by the merchant or fixed to the register), or alternately use his phone’s camera to scan a code generated and presented by the merchant. Accounting for these two distinct interactions, successful designs should facilitate fast scanning while addressing user’s security concerns and need for feedback from the payment experience.

Geolocation

Think of payments using geolocation technology like having an invisible fence around the perimeter of a store . Once the consumer crosses into this perimeter, the merchant is made aware of his presence, facilitating the opportunity for a financial exchange. This could be negotiated through the use of GPS or BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) beacons, depending on the target devices you’d like to support. Mobile payment apps that use geolocation are significant in their lack of interactions, because there is less emphasis on the communication between hardware components as the conduit for a purchase (as seen in the NFC model). Payments in this mode don’t even require the user to pull out his phone if the merchant has been indicated by the user as a “favourite .” Apps like now-defunct Square Wallet and PayPal are designed to work “in the background,” so that a user needs only to open the door of his favourite café to open a tab. The user has a payment source stored in a secure cloud service, which can be charged only if he crosses the merchant’s geofence, or manually makes himself known to the merchant by checking in. With Square in particular, these types of transactions resemble the days when you could walk into your local corner store, and the store owner would know you by name. If you didn’t have any cash on you, you could simply put your bill on a running tab to be settled later.