Comparative Analysis of Optimal Manufacturing Locations for Dubai Lolly’s

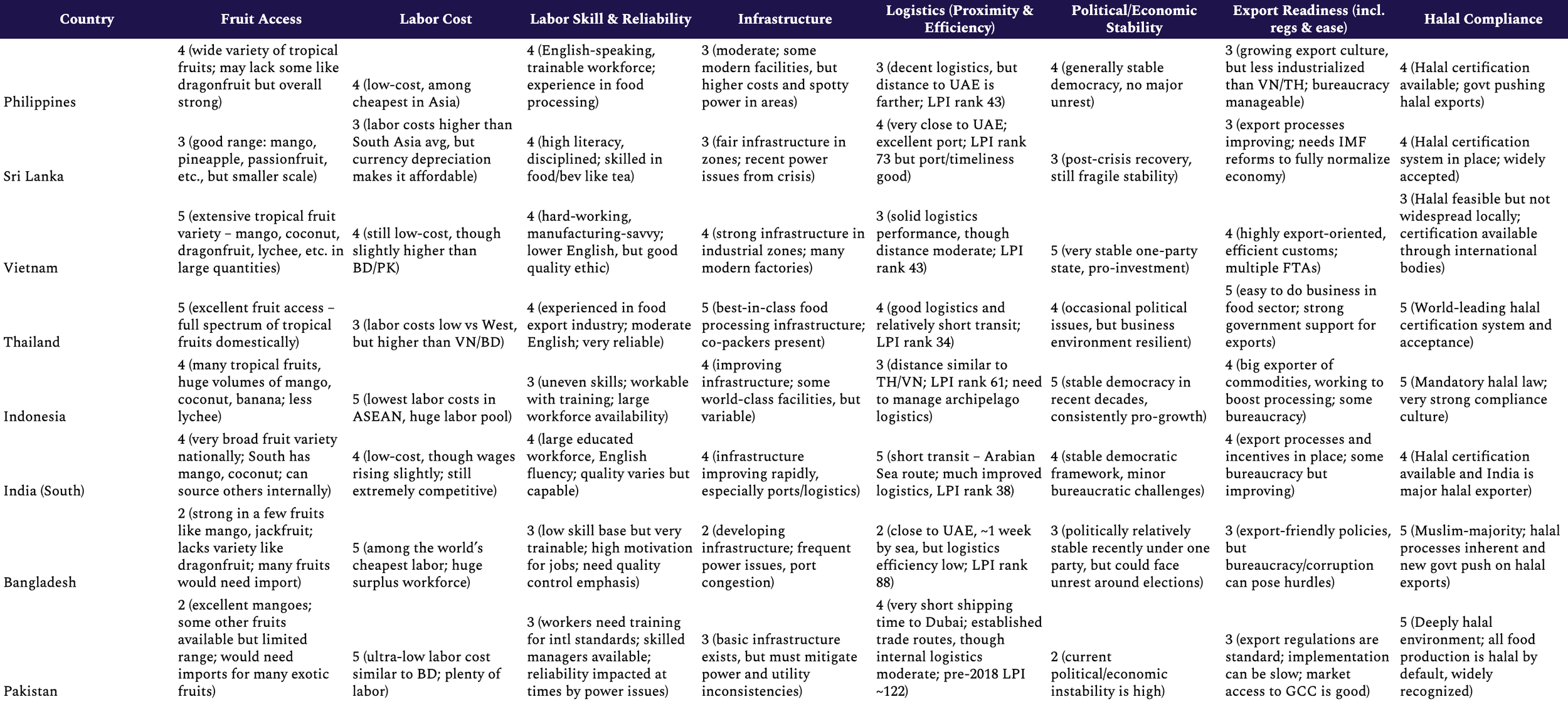

Dubai Lolly’s is a premium frozen dessert brand specializing in Mexican-style paletas infused with Asian tropical fruits, soft fillings, chocolate coatings, and luxury touches (like edible gold). To identify the best country for manufacturing these high-end frozen treats, we evaluate several South and Southeast Asian nations – Philippines, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia, South India (India), Bangladesh, and Pakistan – against key criteria. These criteria include access to tropical fruits, labor cost and skill, food-processing infrastructure (especially co-packing capabilities), logistics and proximity to Dubai (with cold-chain support), political/economic stability, export compliance (halal standards in particular), and scalability for global demand. Below is a detailed comparative analysis, followed by a scoring table summarizing each country’s performance on these dimensions.

Key Criteria for Country Selection

Tropical Fruit Access: The manufacturing base should have abundant local supply of Asian tropical fruits (mango, coconut, lychee, dragonfruit, passionfruit, etc.) integral to Dubai Lolly’s recipes. Ready availability ensures freshness, lower raw material costs, and authentic flavor. Importing missing fruits from nearby countries is a secondary option but adds complexity.

Labor Cost and Skill: Paletas production (fruit processing, filling, coating, packaging) is labor-intensive but also requires food safety and quality skills. An ideal country offers low-cost labor that is reliable and skilled in food handling. High literacy or English proficiency can be a bonus for training and communication. Consistency and hygiene in production are paramount for a premium brand.

Food Processing Infrastructure: The country should have a developed food processing industry or even specialized frozen dessert manufacturing facilities. Existing co-packing (contract manufacturing) options for ice cream/gelato or frozen novelties are a major plus, as they allow faster startup and scalability. Good infrastructure also means dependable utilities (electricity, water) and compliance with food safety standards.

Logistics & Proximity to Dubai: Efficient cold-chain logistics are critical to export frozen products. Shorter transit times to the UAE reduce risk of temperature excursions. Strong shipping connectivity or air freight links to Dubai, availability of refrigerated containers, and high logistics performance (customs, ports, transport) will facilitate smooth export. Geographic proximity (South Asia being closer to UAE than the Far East) can lower shipping time and cost.

Political & Economic Stability: A stable political environment and growing economy provide a secure setting for manufacturing investment. Stability minimizes risks of production disruption (due to strikes, unrest, or policy swings) and ensures consistent operation. Countries recently recovering from crises or experiencing political turmoil may pose higher risks to supply chain continuity.

Export Compliance & Halal Certification: The manufacturing country must easily comply with international food export standards. For Dubai/UAE (and broader Muslim markets), halal certification of ingredients and processes is crucial. The ideal location has established halal certification bodies or a cultural norm of halal food production, ensuring that products can be certified halal (especially if dairy, flavorings, or additives are used). Compliance with other export regulations (quality, labeling, etc.) and a track record of food exports are also important.

Scalability for Global Demand: As Dubai Lolly’s aims beyond the UAE to global markets, the country should allow scaling up production. This entails availability of land/facilities to expand, a large enough workforce, supportive business policies (e.g. export processing zones, incentives), and the capacity to increase output without major bottlenecks. An export-oriented outlook and experience with high-volume production indicate readiness to grow with international demand.

With these criteria in mind, each candidate country is evaluated below.

Country-by-Country Evaluation

Philippines

Fruit Access: The Philippines enjoys a tropical climate and fertile soil, yielding an abundance of fruits. It is a leading global producer of mangoes, bananas, pineapples, and coconuts. Philippine Carabao mangoes are famed among the world’s finest, and the country was the 9th largest mango exporter as of 2010. Coconut is another strong suit – the Philippines is the world’s second-largest coconut producer (after Indonesia), ensuring ample coconut for fillings or creamy bases. Other fruits like jackfruit, bananas, pineapples, and papaya are plentiful. However, lychee and dragonfruit are less common (grown only in limited areas), so those might need to be imported or sourced from local niche farms. Overall, fruit variety is high for core flavors (mango, coconut, etc.), aligning well with the brand’s needs.

Labor: The country offers competitive labor costs by regional standards. In a global ranking of cheapest manufacturing, the Philippines ranks among the top 5 (after India, China, Vietnam, Thailand). Wages for factory workers are significantly lower than in developed countries, roughly on par with Vietnam. Moreover, the workforce is largely English-speaking and literate, which aids in training for food safety and in communicating quality standards. The Philippines has a history of food processing (e.g. dried mango, coconut products), so workers have some relevant skills. Labor reliability is bolstered by a young demographic and cultural familiarity with international food businesses (many Filipinos work in foodservice abroad, bringing back experience). In short, labor is cheap, trainable, and communicative, though productivity can vary and some skilled managerial roles might need development.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: The Philippines’ food processing sector is growing, with major agribusiness firms and some frozen food capabilities. The country has large domestic ice cream producers (e.g. Nestlé Philippines, local brands) and co-packers are emerging. For instance, companies like The Dessert Empire (an OEM dessert manufacturer) are expanding into the Philippines (with a facility “TBA”) to tap regional demand. This indicates interest in using the Philippines as a dessert production hub. The general infrastructure has both strengths and weaknesses. On one hand, there are established processing zones (e.g. in Laguna, Cebu) and improving technology adoption. On the other, energy costs and logistics inside the archipelago can be challenging, and production is somewhat centralized around Luzon. Still, facilities for fruit puree, aseptic packing, and cold storage exist thanks to the fruit export industry. Co-packing availability specifically for frozen paletas might be limited today, but given the country’s push to export more tropical fruit products, a partnership with an existing dairy or ice cream plant could be feasible. Overall infrastructure is moderately developed – capable of supporting a premium product, though possibly requiring some investment in specialized freezing equipment.

Logistics & Proximity: Proximity to the UAE is moderate – the Philippines is in Southeast Asia, which is farther from Dubai than South Asia. Sea shipments from Manila to Jebel Ali (Dubai) typically pass through the Strait of Malacca and can take around 2–3 weeks depending on routing. The country does benefit from being a major exporter of tropical fruits and coconut products, meaning refrigerated shipping is well established. The Logistics Performance Index (LPI) 2023 ranks the Philippines 43rd globally (score 3.3), indicating logistics competence similar to Vietnam and better than many peers. The port infrastructure (notably Port of Manila and Cebu) handles reefer containers, and cold storage facilities are present (for example, for bananas and pineapples bound for Asia and Europe). For air freight, direct flights from Manila to Dubai are frequent (used by Philippine Airlines and Emirates), which is useful for urgent shipments or smaller volumes. While not in the immediate neighborhood of the Middle East, the Philippines has cultivated export routes: it supplies tropical fruit purees and products to markets in the US, EU, and Asia, and UAE retailers (like Lulu Group) have logistics centers in the Philippines to source goods. Cold-chain reliability is decent, but shipping times will be longer than from India or Pakistan. Overall, logistics are adequate, albeit with longer transit times, and the country’s performance in international shipments and customs is middle-tier.

Stability & Business Climate: The Philippines is a stable democracy with a growing economy (~5–7% pre-2020 GDP growth). Recent administrations have been pro-business and infrastructure-oriented. There are no large-scale conflicts; apart from occasional localized unrest, the political climate is predictable. This stability is reinforced by strong institutions and continuous economic reforms. One caveat is the vulnerability to natural disasters (typhoons), which can disrupt agriculture and transport seasonally. Economically, the country is recovering from the pandemic and maintains investment-grade ratings. With the government pushing exports and manufacturing diversification (as seen by DTI’s initiatives to boost exports to the UAE), the business environment is supportive. Labor relations are relatively calm, with fewer strikes in export industries. In summary, the Philippines offers political/economic stability and a friendly investment climate for a manufacturing venture.

Export Compliance (Halal & Standards): As a predominantly Christian nation, the Philippines does not have an innate halal culture, but it is actively developing one. It recognizes the importance of halal certification to access Middle Eastern markets. A national Halal Certification Scheme exists (through bodies like the Islamic Da’wah Council or Philippines Halal Board), and the government has even eyed Mindanao as a “Halal Hub” for food exports. In 2021, the Philippines exported about $6 billion worth of halal-certified food globally, and it has halal accreditation recognized by UAE and other Muslim countries. Filipino companies are increasingly obtaining halal certificates for products like banana chips, processed fruits, etc. While the pool of halal-certified facilities is not as large as in Muslim-majority countries, it is growing – more than 50 Philippine companies were certified for halal by 2023, and partnerships with Gulf retailers (e.g. Lulu) encourage meeting halal standards. Aside from halal, the Philippines complies with international food safety standards (many exporters are ISO 22000 or HACCP certified). English-language documentation and a FDA-modeled regulatory system make compliance straightforward. Halal compliance is attainable with proper oversight, and the country’s export regulations are in line with international norms (BRC, FDA, etc.).

Scalability: With 110 million people and a large agricultural base, the Philippines has significant room to scale production. The presence of export processing zones and incentives (e.g. tax breaks for agribusiness) supports expansion. If Dubai Lolly’s grows in global demand, the Philippines can accommodate larger factories, especially in agro-industrial parks. The government is encouraging investments in food manufacturing, which could ease expansion hurdles. One practical consideration is the power and logistics infrastructure scaling – the grid and port capacity can be stretched, but plans are underway to improve both. The labor pool is ample (over 40 million workforce) and trainable, and automation can be introduced gradually in processes like packing. Given that the country is aiming to capture a larger portion of the $4 billion global tropical fruit market, it is positioned to ramp up output. Thus, for a premium dessert brand, the Philippines offers both current capacity and future scalability, with likely support from government agencies to succeed as an export showcase.

Sri Lanka

Fruit Access: Sri Lanka, as a tropical island, grows a variety of exotic fruits, though on a smaller scale due to its size. Key fruits include mango, pineapple, banana, coconut, papaya, rambutan, mangosteen, and passionfruit. In fact, Sri Lanka exports niche tropical fruits like rambutan, mangosteen, soursop, star fruit, and passion fruit to global markets. Passionfruit is relatively common – passion fruit juice and cordial are popular locally, and it’s cultivated in central regions. Coconut is abundant (an essential part of the agriculture sector), providing coconut milk or cream for fillings. Mango varieties are grown (though not in the quantities of India or Pakistan), and pineapples are cultivated especially for export (Sri Lankan pineapple is known for its sweetness). However, some fruits like dragonfruit or lychee are not traditional crops – any demand for those might need contract farming or imports (dragonfruit cultivation is nascent; lychee doesn’t grow widely in Sri Lanka’s climate). Overall, Sri Lanka can supply many tropical fruits for unique flavors (its portfolio includes lesser-known fruits that could even inspire novel paleta flavors), but total volumes are limited by the country’s smaller land area. For a premium, small-batch brand, local fruit access is sufficient and high-quality, but for very large scale, reliance on imports or expanded farming may be necessary.

Labor: Sri Lanka’s labor force is educated and skilled, with literacy over 90%. Wages are higher than in Bangladesh or India, but after the recent economic crisis and currency depreciation, labor has become relatively affordable in USD terms. The country has a strong tradition in food and beverage manufacturing (tea industry, spice processing, and a few confectionery/dairy plants), so workers are familiar with maintaining quality for export. Labor reliability is generally good – Sri Lankan workers are known for attention to detail (for instance, in tea packing). Additionally, English proficiency is fairly common, easing communication of technical procedures. While absolute labor cost may be slightly above Southeast Asian averages, productivity can offset some cost. Many Sri Lankans also have experience working in Gulf countries’ food sector, which can be valuable if they return with skills. There is also an available pool of cheap labor for manufacturing due to high inflation eroding local incomes – people seek factory jobs to earn stable wages. The government reports that in early 2024, industrial employment rebounded, especially in food manufacturing. In summary, Sri Lanka offers moderately low-cost labor with good skills and a disciplined work ethic, though not the rock-bottom costs of Bangladesh.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: Sri Lanka’s food processing infrastructure is relatively developed for its size, centered around the Western Province (Colombo area). The country has modern facilities for tea, coconut products (desiccated coconut, coconut milk), fruit juices, and an ice cream industry serving the local market. For example, Cargills (Ceylon) runs dairy and ice cream factories, and there are fruit canneries (processing pineapple, mango, etc.) for export. The cold-chain infrastructure is decent – Colombo port has reefer handling capacity, and there are cold storage warehouses (partly to serve fisheries export). Co-packing facilities specifically for frozen desserts might not be readily established, but the presence of major food conglomerates means contract manufacturing could be negotiated. Additionally, Sri Lanka has free trade zones (e.g. Katunayake, Biyagama) that host food and beverage processing plants; a foreign brand could set up in such a zone with tax benefits and ready utilities. Power supply was a concern during the 2022 crisis, but by late 2023, the situation stabilized (electricity shortages have eased after reforms). Transportation infrastructure is quite good – an extensive road network and proximity of factories to ports/airports (it’s a small island, so transit is quick). Given these factors, Sri Lanka’s infrastructure can support a high-quality, small to medium scale production of premium paletas. Any specialized machinery (continuous freezers, flow-wrappers for bars) might need import, but installing them in existing food plants is feasible. Overall, the infrastructure is competent but on a limited scale – suitable for a premium niche product but not geared for massive volumes without further investment.

Logistics & Proximity: Sri Lanka is geographically close to Dubai – sitting near major Indian Ocean shipping lanes. Shipping time from Colombo to Jebel Ali Port is relatively short (perhaps 4–7 days by sea), which is a significant advantage for frozen goods. The Port of Colombo is a world-class transshipment hub and was ranked among the top 25 ports globally in container throughput. It has excellent connectivity to the Middle East, with many vessels making direct calls or quick transshipments. In terms of logistics performance, Sri Lanka’s LPI 2023 rank was 73 (score 2.8), which is lower than larger peers due to the crisis impact, but the port and timeliness scores are relatively strong. Cold-chain logistics to the Middle East are proven: Sri Lanka exports seafood and fruits to Gulf markets frequently, requiring temperature-controlled shipment. Air freight is another option – Colombo has direct cargo flights to the UAE (and numerous passenger flights daily that can carry freight), making it viable to fly urgent shipments of high-value frozen desserts if needed. Domestically, the short distances mean fruits can be transported from farm to factory quickly under refrigerated conditions, preserving quality. Additionally, Sri Lanka has bilateral and regional trade ties: it’s part of SAARC and enjoys good relations with GCC importers. Proximity and top-notch port facilities give Sri Lanka an edge in logistics, though one must note that the economic turmoil in 2022 caused some supply chain hiccups (fuel shortages for trucks, etc., now largely resolved). At present, with IMF-backed stabilization, logistics fuel and operations are normalizing. In summary, Sri Lanka offers efficient cold-chain logistics and short transit to Dubai, a key benefit for maintaining product quality.

Stability & Business Climate: Sri Lanka recently navigated a severe economic and political crisis in 2022. The country defaulted on debt and saw mass protests that ousted the president. However, since late 2023 the situation has stabilized due to reforms and IMF support. By 2024, the economy returned to modest growth (5% in Q1 2024) with inflation under control. Political stability has improved under the new government, though the recovery is fragile and upcoming elections could introduce uncertainty. For a foreign investor, Sri Lanka historically has a welcoming business environment (high literacy, strong legal framework, and protection of foreign investments), and it is rebuilding that reputation. There remain risks: high public debt (still under restructuring), the need to maintain social stability during reforms, and potential policy changes with a new election. On the positive side, the crisis prompted a drive for export-led growth and efficiency, which could benefit ventures like food manufacturing. The government is keen on attracting FDI to generate jobs and dollars, so a project like Dubai Lolly’s could find supportive policies. In terms of safety and rule of law, Sri Lanka is generally safe and has stable institutions (Central Bank, judiciary, etc.), albeit with some bureaucratic red tape. Political risks are moderate – not as low as in Vietnam or UAE, but Sri Lanka is not in conflict or chaos, just in economic recovery. If one is willing to navigate short-term uncertainties for potentially lower competition and costs, Sri Lanka can be a strategic choice.

Export Compliance (Halal & Standards): Sri Lanka has a multi-religious society (about 9% Muslim) and a functioning halal certification framework. The halal certifier was traditionally the All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama (ACJU), which certifies food products and factories for Islamic compliance. There was a brief controversy in 2013 over halal domestically, but this was resolved by streamlining the process under the national standards body. Now, many Sri Lankan food exporters (tea, confectionery, meat) carry internationally recognized Halal certificates, often overseen by the Halal Accreditation Council of Sri Lanka. For example, leading exporters of processed food ensure halal compliance to sell in Malaysia or the Middle East. Thus, obtaining halal certification in Sri Lanka is straightforward, and the country’s halal logo is accepted in Gulf markets. Additionally, Sri Lanka’s food exports meet stringent quality standards – factories follow ISO 22000, BRC, etc., especially those in export processing zones. The country is reputed for ethical tea and spice production, which implies good manufacturing practices. Sri Lanka is also OIC (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) compliant in spirit as it exports to OIC countries regularly. The halal compliance and export standards are well in place: e.g., the nation exported halal-certified foods (like halal meats, gelatins, etc.) and even has government support to boost halal product exports. Any product leaving Sri Lanka for Dubai will go through routine quality and halal checks, and with its free trade agreement with Pakistan and close ties to GCC, compliance is not a hurdle.

Scalability: As a smaller country (22 million people), Sri Lanka’s capacity for very large-scale production is naturally limited compared to giants like India or Indonesia. However, for a premium niche brand, Sri Lanka can scale to meet international demand up to a point. The strategy would likely involve leveraging multiple facilities: one could expand within an export zone or partner with multiple co-packers to increase output. The land area in existing industrial zones is finite, but new zones (like Hambantota) are being developed that could host larger food processing parks. The availability of labor might tighten if trying to scale up massively, since many skilled workers emigrate for higher wages; nonetheless, unemployment rose during the crisis, so there is slack in the labor market now. Infrastructure scalability might be a constraint – the power grid and ports can handle moderate growth, but if production needed to, say, increase tenfold, it could strain resources without upgrades. On the market side, Sri Lanka’s government would welcome an expanding export operation, possibly offering incentives for expansion. Financing expansion might be costlier locally due to high interest rates, but foreign capital could fill that gap. In essence, Sri Lanka is ideal for small to medium scale premium production. It can scale gradually (double or triple output) with efficiency improvements and maybe shift to higher automation if labor becomes scarce. For truly massive production volumes, one of the larger countries might be better suited. But if Dubai Lolly’s is targeting a high-end segment globally, Sri Lanka can likely meet demand while maintaining superior quality, given its focus on exotic, high-value exports.

Vietnam

Fruit Access: Vietnam stands out for its rich variety of tropical fruits. Thanks to diverse climates from north to south, Vietnam can produce over 50 types of fruits on a large scale. It is one of the few countries that grow nearly all fruits of interest: mangoes, coconuts, dragon fruit, passionfruit, longan, lychee, rambutan, durian, pomelo, banana, and more. Notably, Vietnam is the world’s largest producer of dragon fruit (a signature export crop from Binh Thuan Province) and a major supplier of lychee and longan (grown in the northern provinces). In 2024, Vietnam’s fruit export revenue hit a record $7.15 billion, driven by booming durian, coconut, longan, mango, and dragon fruit shipments. This indicates a robust fruit industry with year-round availability – for instance, dragon fruit can be harvested nearly year-round for export For Dubai Lolly’s recipes, Vietnam offers every core fruit ingredient domestically: juicy tropical mangoes, young coconuts, fragrant lychee, vibrant dragon fruits, and tart passionfruit (now widely grown in the Central Highlands). The concentration of fruit farms and Vietnam’s experience in exporting these fruits (fresh and processed) mean input supply is not only broad but also export-quality and scalable. The country even processes fruits into purées and fillings – less than 14% of fruit export revenue is processed currently, but capacity is growing, aligning well with making paleta mixtures. In summary, Vietnam offers excellent tropical fruit access – arguably the strongest among the candidates – covering all flavor needs with local produce

Labor: Vietnam is known for affordable, diligent labor. It has become a global manufacturing hub partly due to labor cost advantages. Vietnamese labor is more affordable than many regional counterparts; the average manufacturing wage (~$733 per month) remains far lower than in China or Malaysia. Although its wages have risen with economic growth, Vietnam still ranks among the lowest labor-cost countries for manufacturing (often cited just after India and China in surveys). Importantly, Vietnamese workers have a reputation for being hard-working and quick learners. The country’s education system ensures high literacy (over 95%) and technical training is improving. In food production, Vietnam’s workforce has experience with stringent standards thanks to its large seafood processing industry and growing food export sector. Many factories (seafood, cashew, coffee) are concentrated in the south, where a culture of factory discipline has developed. Labor reliability is good, with relatively few labor strikes (compared to some neighbors) and a strong work ethic fostered by the government. On the skill side, while English proficiency is not as common on the factory floor, supervisors and engineers are increasingly fluent. Training materials can be translated and effectively taught. Vietnam also invests in food safety training as it expands exports (e.g., workers are trained to meet US/EU standards for fish and fruit exports). Thus, Vietnam provides low-cost labor ($) with growing skill and reliability. The main challenge might be managerial skill shortages, but foreign firms often bring in some management or upskill locals quickly. Overall, for consistent quality in paleta production, the Vietnamese workforce can deliver when guided properly.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: Vietnam’s infrastructure has modernized rapidly, especially in manufacturing zones. The country boasts 150+ fruit and vegetable processing factories with modern tech and ~1.1 million tons/year capacity – indicative of its readiness for large-scale food processing. Industrial parks near Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi are well-equipped with utilities. The cold-chain infrastructure is decent and improving: cold storage facilities, reefer trucking, and port refrigeration are in place due to heavy exports of seafood, fruits, and other perishables. As for co-packing, Vietnam has attracted foreign investments in food processing (for instance, Nestlé has factories for coffee and dairy drinks, Korean and Japanese firms process seafood and snacks). While specific frozen dessert co-packers are not widely advertised, there are companies in neighboring Thailand and Malaysia that could extend services to Vietnam, or Vietnamese dairy companies like Vinamilk and Kido Group (which makes ice cream for local market) that might take on contract manufacturing. Vietnam’s government encourages value-added food exports, so setting up a production line for frozen paletas is feasible – machinery can be imported duty-free under investment incentives, and there is a network of equipment suppliers and engineers in the country. Moreover, infrastructure indices reflect this progress: Vietnam’s infrastructure quality score in LPI is 3.2 (47th rank), comparable to far richer countries. The country has already hosted sophisticated processes – for example, fruit irradiation facilities for exports to the US, and modern breweries, showing technical capability. One limitation is that refrigeration technology expertise in Vietnam might not be as deep as in Thailand; however, given clear requirements, the environment can support a state-of-the-art frozen dessert plant. Overall, Vietnam’s infrastructure is strong and geared for export manufacturing, requiring only moderate setup effort to produce premium frozen desserts.

Logistics & Proximity: Vietnam is located in Southeast Asia, farther from Dubai than South Asian countries, but it compensates with improving logistics performance. It ranked 43rd in the 2023 LPI (score 3.3), on par with countries like the Philippines, and its logistics are continually advancing. The main seaports (Ho Chi Minh City’s Cat Lai, and Cai Mep deep-sea port, plus Hai Phong in the north) handle large volumes of exports and are connected to major shipping routes. For the Middle East, most Vietnamese exports currently go via transshipment hubs like Singapore or Colombo. Notably, the UAE (Dubai) is already an importer of Vietnamese fruits – the UAE is listed among the top 10 importers of Vietnam’s fruits and vegetables. This means logistics channels to Dubai exist and can be leveraged, though often via re-export hubs. Transit times by sea from Vietnam to Dubai might be ~10–14 days. Cold-chain wise, Vietnam exports dragon fruit, rambutan, etc., by sea to markets as distant as Europe, so maintaining frozen paletas for a ~2-week journey is technically manageable with proper reefer containers. Air freight options are available too: there are direct flights (passenger and cargo) between Vietnam and UAE (e.g., Emirates flies from both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, and Vietnam’s carriers could carry cargo). However, air freight cost is high for frozen goods, so sea is preferred for volume. Internally, getting raw fruits from farm to factory has improved with new highways in the Mekong Delta and cooler trucks (the government has focused on reducing produce loss). Vietnam’s international shipment ranking jumped to 22nd for timeliness in the LPI, reflecting fewer delays. Customs procedures have modernized (e-customs clearance, etc.), which helps export efficiency. The main disadvantage remains the distance – being further than India/Pakistan means higher shipping costs and time. But given Vietnam’s proficiency in exporting perishables (even to demanding markets like Japan, US, EU), the logistics are reliable, if not the absolute fastest to UAE. In short, Vietnam offers efficient logistics and a growing cold-chain network, albeit with longer transit to Dubai compared to South Asia.

Stability & Business Climate: Vietnam is politically very stable. As a one-party socialist republic, there are no sudden changes in government policy; the leadership has consistently focused on economic growth and attracting FDI. This stability has made Vietnam a favored manufacturing destination. Social unrest is minimal (dissent is tightly controlled), and there are no internal conflicts. The economy is strong (6-7% growth typical in pre-2020 years, rebounding post-COVID) and welcoming to foreign investors through liberalized trade policies and multiple free trade agreements. Vietnam’s rise in ease-of-doing-business rankings and its robust handling of logistics and industrial development illustrate its investor-friendly climate. The currency (dong) is relatively stable, and the government offers tax holidays for projects in high-tech or agriculture processing sectors. One consideration is that bureaucracy can still be tricky – regulatory compliance takes time, and informal norms may require relationship-building. However, compared to the volatility seen in Pakistan or even India’s complex bureaucracy, Vietnam is often seen as straightforward: many multinational food companies (Nestlé, CJ, Maruha, etc.) operate successfully. Intellectual property is reasonably protected (important for proprietary recipes), and corporate laws allow full foreign ownership in manufacturing. In summary, Vietnam’s political-economic stability is high, and its policy environment is geared towards exporting industries. The main risk to note is over-concentration: the government can make sudden sector-wide decisions (for example, strict COVID lockdowns in 2021 hit factories hard). But those events are exceptions; overall, Vietnam’s stability is a strong asset in ensuring uninterrupted operations.

Export Compliance (Halal & Standards): Vietnam is not a Muslim-majority country, but it has adapted to requirements of Muslim markets as its exports grow. Halal certification in Vietnam is available through various international and local certifiers (e.g., halal certification bodies from Malaysia, Singapore, or the local Muslim community). As of now, Vietnam’s domestic halal ecosystem is smaller – only about 0.1% of its population is Muslim (mostly in the south and among the Cham minority). Despite this, Vietnamese companies have obtained halal certificates to export food (for example, Vietnamese seafood, coffee, and even instant noodles are sold in the Middle East with halal logos). The government, recognizing the opportunity, has encouraged firms to pursue halal accreditation and even hosted halal trade fairs. For a frozen dessert that likely contains dairy and fruit (all plant-based or from cow milk), meeting halal standards mainly involves ensuring no alcohol-based flavorings, no porcine gelatin (use plant stabilizers), and that the factory avoids cross-contamination with any haram items. This is quite feasible in Vietnam – many factories are dedicated to specific product lines. If needed, supervisory halal inspectors can be brought from Malaysia or Indonesia to certify the process. Apart from halal, Vietnam’s export standards for food have improved markedly. Factories aiming for export commonly implement HACCP and ISO 22000, and Vietnam’s Ministry of Agriculture works with exporters to meet SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) standards of different countries. The country now exports fresh fruit to demanding markets like the US and Australia, which requires strict compliance (including treatments like vapor heat and irradiation). That expertise translates into a general culture of compliance with international norms. Therefore, while Vietnam doesn’t have a pervasive halal environment by default, it can readily comply with halal certification for an export line, and it certainly meets global quality and safety standards expected for a premium product.

Scalability: Vietnam offers high scalability potential for production. Its manufacturing sector has boomed by accommodating both small and very large operations (from family-run factories to Samsung’s massive electronics plants). For Dubai Lolly’s, starting with a certain capacity and scaling up is facilitated by Vietnam’s deep labor pool (98 million population) and expanding industrial infrastructure. If demand surges globally, one could increase shifts or build additional lines in Vietnam relatively quickly. The government often supports expansions by quick approval of permits in industrial zones. Also, Vietnam’s significant domestic market (nearly 100 million consumers) could absorb product if one chooses to also sell regionally, providing a secondary market that justifies larger production runs. The presence of multiple port options (north, central, south) means one could even have split production sites if needed. One area to watch is labor availability in certain hotspots – in recent years, some coastal manufacturing zones have faced labor shortages and had to import workers from other provinces. But automation can augment labor if scaling up a lot (e.g., using automated filling and wrapping machines for popsicles). Vietnam has shown the ability to scale in the food sector – e.g., seafood exports scaled to billions of dollars with hundreds of factories across the Mekong Delta. Similarly, fruit processing is now being ramped up as processed fruit exports still only account for <14% of total fruit exports (indicating room to multiply processing capacity). The country’s push for industrialization means any successful pilot facility can attract more investment, possibly government grants for expansion. In conclusion, Vietnam can start with modest production for a premium brand and scale to very large volumes if needed, leveraging its workforce and pro-growth policies – making it one of the strongest candidates in terms of long-term scalability.

Thailand

Fruit Access: Thailand is another fruit powerhouse of Asia, often called the “Kitchen of the World.” It produces a wide spectrum of tropical fruits abundantly: mangoes, coconuts, pineapples, bananas, mangosteen, rambutan, longan, lychee, durian, jackfruit, and more. In fact, Thailand’s climate allows multiple fruit harvests per year and a diversity from north (temperate fruits and lychee/longan) to south (coconut, durian, etc.). It is a top global exporter of fruits like durian and longan. By value, Thai fruits exports were significant – in 2021/22, Thailand exported nearly $6 billion in halal-certified food including processed fruits and veggies. Key for Dubai Lolly’s, Thailand can locally supply all the fruits mentioned: mango (Thai Nam Dok Mai mango is famous), coconut (Thailand has vast coconut plantations in the south), lychee (grown in the northern highlands of Chiang Mai), dragonfruit (not native, but now cultivated and also easily imported from Vietnam next door to supplement), and passionfruit (grown in northern and northeastern Thailand; plus passionfruit products are made for juices). The Thai fruit industry is well-developed – fruits are sold fresh, frozen, dried, pureed, candied, etc. The country even has R&D into new fruit varieties and processing techniques. This means a manufacturer can procure both fresh fruits and fruit ingredients (purees, concentrates) from local suppliers. For example, for a paleta with soft mango filling, one could source Thai mango purée which is readily available. Edible gold and other luxury garnishes can also be sourced in Thailand (Bangkok has a gold industry for food decor). In summary, fruit variety and availability in Thailand are excellent, with essentially every tropical fruit either grown domestically or easily accessible via its well-connected import market.

Labor: Thailand’s labor market is considered moderately low-cost and highly experienced in food manufacturing. While Thailand is not the absolute cheapest in ASEAN (its wages are above Vietnam’s or Indonesia’s), it is still significantly lower-cost than China or Western countries. Thai labor also benefits from higher productivity and skill due to decades of industrialization. Many Thai workers have long experience in processing foods for export (seafood, canned fruits, rice snacks, etc.), which means they are trained in hygiene, efficiency, and meeting standards. Additionally, Thailand has a sizable migrant labor population (from Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos) that often works in food factories for relatively low wages, increasing the available workforce for labor-intensive tasks. Reliability of labor is generally high – Thai factory culture emphasizes order and cleanliness (likely influenced by major international firms present). Thai workers are also known for creativity in food (which could be a plus in product development). English proficiency at the worker level is limited, but supervisors and technicians often have some command of English, especially in firms exporting globally. Labor laws in Thailand are fairly employer-friendly, and industrial relations are stable (occasional strikes happen but infrequent). Sphere Research notes that Thailand’s labor costs, while not the cheapest, remain much lower than China’s and firmly in the “low-cost bracket” for manufacturing. Considering the skill-to-cost ratio, Thailand offers efficient labor for a slightly higher price than Vietnam/Bangladesh – a trade-off often worth it for high-quality output. For a premium dessert, the consistency and skill in handling food safely might justify Thailand’s moderate wage premium.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: Thailand boasts one of the most advanced food processing industries in Asia. It’s a global top 15 food exporter and has a comprehensive ecosystem of processing facilities, cold storage, packaging suppliers, and machinery dealers. For frozen desserts specifically, Thailand has relevant infrastructure: for example, a Thai company (AFC) produces Bud’s Ice Cream under license in Bangkok and offers co-packing for ice cream cakes and novelties. This indicates that ice cream co-packing services exist in Thailand, which could potentially extend to paletas or be adapted for them. Moreover, The Dessert Empire (a regional OEM) lists a major dessert manufacturing hub in Thailand (Samut Prakan) which services global brands with gelato, soft serve, etc. These are promising signs that a partner could be found to produce Dubai Lolly’s in Thailand without starting from scratch. Infrastructure-wise, Thailand has excellent road and port networks. Industrial zones (like those around Bangkok, Chonburi, Rayong) have reliable power, water treatment, and logistics support. The country is also a packaging hub – advanced food-grade packaging (wrappers, sticks, etc.) can be sourced locally. Cold-chain technology is mature: Thailand exports billions in frozen seafood and prepared foods, so it has large-scale blast freezers, cold storage warehouses, and expertise in maintaining frozen supply chains. The machinery for making paletas (freezing tunnels, molds, etc.) could be imported easily and serviced locally – Thailand has many distributors of Italian and Japanese food machinery. On quality, Thai factories often hold BRC, ISO22000, and similar certifications, reflecting high standards. In summary, Thailand’s infrastructure is top-notch for food manufacturing, and the presence of known co-packers and OEM dessert manufacturers makes it arguably the easiest location to start production with minimal delay.

Logistics & Proximity: Thailand’s logistics capabilities are high and distance to UAE is intermediate. The World Bank’s LPI 2023 ranks Thailand 34th globally (score 3.5), even above India and on par with many EU countries. This high ranking is due to efficient customs, good infrastructure, and timely shipments. For exports to Dubai, Thailand has regular shipping routes: Thai fruits, rice, and electronics routinely ship to the Middle East. While not as geographically close as India, Thai shipments transit via the Indian Ocean (often through Colombo or Singapore). Sea transit time from Laem Chabang (Thailand’s main port) to Jebel Ali is around 10–12 days. Thai exporters are adept at handling perishable shipments – for instance, Thai mangosteens and mangoes reach Middle East markets by air and sea, maintaining quality. Cold-chain logistics inside Thailand is supported by numerous refrigerated trucking companies and the country’s “Cool chain” initiative to ensure freshness from farm to port. Air connectivity is also excellent: Thai Airways and Middle Eastern airlines operate daily flights between Bangkok and UAE, useful for emergency or small shipments of high-value products. Additionally, Dubai is a major re-export hub for Thai goods; trade ties are strong, and Thai companies often exhibit at Gulf food expos. Proximity-wise, Thailand is closer than the Philippines/Vietnam but farther than India. However, given Thailand’s logistics efficiency, the slightly longer distance is mitigated by highly reliable and fast handling. For example, goods can leave a Thai factory and be on a vessel within a day or two, given streamlined procedures, which keeps total delivery time reasonable. Moreover, halal logistics (ensuring no cross-contamination in transit) are practiced since Thailand exports many halal foods to OIC markets. Overall, Thailand provides fast, dependable logistics and cold-chain management, with only moderate transit times to Dubai as a downside.

Stability & Business Climate: Thailand’s political situation has had turbulence (coups in 2014, protests in recent years), but the country’s economy and business environment have proven resilient. Despite changes in government, the fundamental policies toward foreign investment and exports remain positive. The Thai civil service and Board of Investment ensure continuity of pro-business measures even during political transitions. Therefore, operationally, Thailand is considered stable for businesses. The economy is diversified and robust, weathering global shocks well. One should note that there is some risk of unrest (e.g., protests in Bangkok), but these rarely impact industrial operations outside the capital. The rule of law for commerce is well-established (Thailand has strong investor protections, property rights, etc.). The country ranks high in ease of doing business, especially in protecting minority investors and trade across borders. For a foreign company, 100% ownership is allowed in many sectors (food manufacturing can get BOI incentives with tax breaks and land lease benefits). Additionally, Thailand’s workforce is fairly stable – there are migrant labor management issues, but nothing that critically threatens production. Economically, the Thai baht is stable and inflation moderate, giving cost predictability. One area of advantage is Thailand’s government support for the food industry: they actively brand the country as a global food production hub, which aligns well with an incoming premium brand – support could come in the form of facilitation, networking, or even subsidies for value-added food exporters. In summary, while Thailand has periodic political changes, it maintains a stable, predictable business climate and a continuity in economic policies that favor manufacturing and export.

Export Compliance (Halal & Standards): Thailand is a global leader in halal food exports despite its Buddhist majority. The country ranked 11th in the world by halal food export value in 2023, with over 160,000 products and 14,000 companies halal-certified. Thai halal standards are internationally recognized – the Central Islamic Council of Thailand (CICOT) and Halal Standard Institute (HSIT) rigorously ensure Thai halal products meet OIC guidelines. They combine “religious confirmation and scientific support” to detect any haram substances in ingredients. As a result, Thailand’s halal certificate is globally accepted, and the nation prides itself on having the highest number of halal-certified products in the world. For Dubai Lolly’s, this means if production is in Thailand, obtaining halal certification would be straightforward and credible to Middle Eastern consumers. Many Thai food factories already operate under halal rules (e.g. use halal gelatin, segregate any non-halal lines or avoid them entirely). Beyond halal, Thai exports are synonymous with quality – Thailand’s food safety regulations are stringent, and exporters comply with US FDA, EU, and Gulf standards. The country has agencies to help firms with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and certifications like HACCP. Given that major global retailers import Thai foods, compliance with labeling, traceability, and quality is ingrained. Also, as an established exporter, Thailand faces fewer inspections or holds at foreign customs due to trust built over years. In essence, Thailand excels in export compliance: it offers an easy path to halal certification (critical for Muslim markets) and upholds high international standards in production.

Scalability: Thailand has a mature industrial base with the capacity to scale production significantly. If Dubai Lolly’s chooses Thailand, it can start modestly and expand as needed, leveraging Thailand’s extensive network of suppliers and factories. The country’s relatively higher labor cost is offset by its ability to automate and improve efficiency as scale grows. Large-scale production is routine in Thailand’s food industry – from packing millions of cans of tuna to processing vast quantities of chicken for export. This means the know-how to manage a growing operation (sourcing larger volumes of fruit, maintaining quality over bigger batches, etc.) is available. Infrastructure will not be a bottleneck; the power grid is stable and can handle industrial loads, and ports can manage increased shipping volumes easily. Industrial land is also available – new factories can be built in numerous industrial estates if needed, often with fast approval. Moreover, the presence of co-packers implies that scaling might be as easy as contracting additional volume to them or adding production shifts. If demand skyrockets, one could even distribute production – for example, produce some flavors in one plant and others elsewhere – which is feasible given Thailand’s connectivity. Financially, local banks and investors are comfortable financing expansion in the food sector, and the BOI might grant incentives for scaling up export production (like machinery import duty exemptions, extended tax holidays, etc.). The only potential limitation is labor availability if very large expansion is needed, but Thailand can adjust by either bringing more migrant workers or investing in automation (it’s already moving towards more automation in repetitive tasks). Given these factors, Thailand provides a highly scalable environment – from small artisanal batches up to mass production for global distribution – all while maintaining consistent quality.

Indonesia

Fruit Access: Indonesia, with its vast archipelago spanning the equator, has tremendous tropical fruit resources. It is the world’s largest producer of coconuts and a leading producer of mangoes, bananas, and pineapples (many statistics include Indonesia at the top ranks for these fruits). Key fruits such as mango are grown extensively (e.g., the Harumanis mango from Java), and coconut plantations are abundant across Sumatra, Java, and Sulawesi – ensuring ample coconut milk, water, or flesh for paletas. Bananas and pineapples are cultivated on a large scale (with some pineapple estates in Sumatra supporting a canning industry). While Indonesia is not as famous for lychee or longan (those prefer subtropical climates not common in Indonesia), some highland areas might grow them minimally. Dragonfruit has been rapidly adopted by Indonesian farmers in recent years (especially in Java and Bali), due to regional demand; similarly, passionfruit (called markisa locally) is grown in Sumatra (Medan is known for passionfruit syrup), and in parts of Java. Additionally, Indonesia offers exotic fruits like mangosteen, rambutan, salak (snakefruit), soursop, jackfruit – these could even inspire unique flavors or fillings for a premium brand. The diversity is huge across 17,000 islands, although logistics of gathering them can be complex. Still, major fruit production centers on Java and Sumatra are well connected. Given its size, Indonesia can provide high volumes of fruits: for example, during season, a single Indonesian province can produce thousands of tons of mango or durian. For Dubai Lolly’s core fruits, Indonesia mostly has them (except lychee might be an outlier). The country’s fruit export profile is growing too (it trains farmers to meet export standards, e.g., mangosteen to China). In summary, Indonesia has rich tropical fruit access, enough to supply ingredients for a premium paleta brand in both variety and quantity. Minor gaps (like lychee) could be filled by imports from neighbors, but overall fruit sourcing in Indonesia would be robust.

Labor: Indonesia boasts the lowest manufacturing labor costs in Southeast Asia, approximately one-fifth of China’s labor cost. This ultra-low cost makes it very attractive for labor-intensive production. The workforce is large (Indonesia has 270+ million people) and relatively young. Skill levels vary: there is a segment of well-trained workers in modern factories (automotive, electronics), while a huge portion of labor remains unskilled or semi-skilled in agribusiness. In food processing, Indonesia has established itself in sectors like fish processing, palm oil, and instant noodles, so there is a base of workers familiar with food safety requirements. However, maintaining strict hygiene and quality for a luxury product may require robust training – Indonesia has had occasional challenges with consistency (for instance, varying quality in some export products). That said, major multinationals like Nestlé, Danone, and Unilever operate many factories in Indonesia (including ice cream and dairy plants), proving that Indonesian labor can meet high standards under good management. The advantage is that labor is plentiful and very cheap, meaning one can employ more workers for tasks that might be automated elsewhere, potentially achieving a hand-crafted quality. Reliability in terms of attendance and productivity is generally good, though in remote areas it can be affected by local culture and infrastructure issues. English proficiency on the line is low, but supervisors often understand some, and manuals can be in Bahasa Indonesia. Additionally, labor laws are reasonably flexible after recent reforms, allowing easier hiring/firing and use of contractors, which help adapt workforce size as you scale. In conclusion, Indonesia offers extremely low-cost labor and a massive labor pool, with adequate skill that can be honed for premium food production given the country’s experience with big food companies.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: Indonesia’s infrastructure is mixed: main cities and industrial zones have good facilities, but remote areas are less developed. For a frozen dessert operation, one would likely situate in West Java or around Jakarta – these areas have industrial estates with solid infrastructure (electricity, water, waste management) and proximity to ports. The country’s largest ice cream factory (by the Chinese dairy giant Yili) recently opened in West Java, touted as the largest ice cream facility in Southeast Asia, featuring advanced automation and digital tech. This indicates that Indonesia can host state-of-the-art frozen dessert production. Co-packing in Indonesia is present in some sectors (e.g., there are contract manufacturers for snacks, beverages), though not widely advertised for ice cream. However, given Yili’s presence and other local brands (Campina, Indoeskrim, Walls by Unilever), there are certainly knowledgeable professionals and possibly spare capacity in some plants for contracting. Additionally, The Dessert Empire lists an Indonesian branch in Tangerang, implying that their Southeast Asian frozen dessert manufacturing network includes Indonesia – possibly for distribution within the country or region. This could be a direct co-pack opportunity. Cold storage and cold transport facilities are growing: Jakarta and Surabaya have large cold storage providers (used for fish, meat exports). The main gap historically was infrastructure quality – roads and ports were congested. But recent investment has improved key logistics routes (new toll roads, port expansions). The Logistics Performance Index (LPI) 2023 ranked Indonesia 61st (down from 46th in 2018), citing room for improvement. However, for an export-oriented facility, one can mitigate infrastructure issues by choosing a well-established industrial zone near Port of Tanjung Priok (Jakarta). The Indonesian government also offers bonded zones and free trade zones (e.g., Batam) which have better infrastructure. In summary, Indonesia’s infrastructure can support a modern frozen dessert operation if placed in the right location, and co-packing options likely exist via regional OEMs or partnerships with existing ice cream producers. The country might require a bit more setup effort than Thailand or Vietnam due to bureaucratic and infrastructure quirks, but the fundamentals (power, facilities, knowledge) are there especially in Java.

Logistics & Proximity: Indonesia is moderately distant from Dubai – similar to Vietnam/Thailand in needing about 12–15 days by sea. Jakarta to Dubai shipping routes often go via Singapore or Colombo. Internally, logistics have challenges given Indonesia’s geography; sourcing fruits from different islands might need inter-island shipping or a supply chain strategy (e.g., focusing on Java’s own fruit production or importing fruits from neighbors rather than collecting domestically from far-flung islands). Despite this, Indonesia is a major exporter of perishable goods (e.g., seafood, tropical fruits like mangosteen, and also processed foods to the Middle East). It has cold-chain capabilities: refrigerated containers and carriers are used for fish exports to Europe and tuna to Japan. The proximity advantage to Dubai is less than for India/Pakistan, but not significantly worse than other ASEAN countries. Additionally, Indonesia has strong trade links with the Middle East – the UAE imports Indonesian products (like palm oil, coffee, cocoa) and Indonesia imports oil; this has led to established shipping lines. In fact, Middle Eastern demand for Indonesian tropical fruits like snakefruit and mangosteen is growing, indicating that specialized fruit cargo already moves on this route. Air connectivity: Garuda Indonesia and Emirates/Etihad have flights between Jakarta and UAE, which can carry freight if needed urgently. Politically, Indonesia and UAE have enhanced economic ties (talk of an Indonesia-UAE CEPA, Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement), which should streamline trade. One area to note: port efficiency in Indonesia can be lower – as the LPI suggests, customs and clearance can be slower than in say, Thailand. However, there have been improvements (Jakarta’s port dwell times have reduced in recent years). Cold-chain risk during these potential delays can be mitigated by using reliable freight forwarders and shipping lines – many global liners operate in Jakarta with modern reefer monitoring. Overall, Indonesia’s logistics are adequate but not top-tier; careful planning can ensure smooth cold-chain export to Dubai, though one might face slightly more variability in timelines.

Stability & Business Climate: Indonesia is a stable democracy with predictable progress. Since 1998’s reforms, it has had peaceful transitions of power and a steady policy environment favoring economic growth. Current political risk is low, aside from normal election cycles (the next presidential election is 2024, but all likely contenders are market-friendly). Social stability is good, with occasional local unrest but nothing systemic that affects business broadly. The economy is one of the G20, offering a large, growing market and reasonably sound macroeconomic management (debt levels moderate, investment grade ratings). For foreign investors, Indonesia can be bureaucratic – permits and licenses can take time, and there are some restrictions (e.g., foreign ownership rules) but the government has been easing these through omnibus laws. The 2023 LPI drop to 63rd partly reflects pandemic disruptions, not a fundamental instability. Indeed, by 2025 Indonesia is expected to be among the top 5 global economies (PPP basis), indicating confidence in its stability. A plus is economic resilience and scale – even if one region faces an issue, there are alternatives (e.g., if one province has a disruption, others keep running). Corruption and red tape remain challenges; partnering with a local firm or hiring experienced local managers helps navigate these. But many international companies operate successfully in Indonesia’s food sector (e.g., Coca-Cola’s largest ASEAN bottling operations are there), which shows the climate is manageable. Regarding specific stability factors: no war, no extreme political unrest, and a general pro-investment stance (especially trying to woo investment away from China). Indonesia also enjoys good relations with the UAE, recently signing deals that could enhance investor protections. In summary, Indonesia offers a stable and large economy for manufacturing, with the main caveat being bureaucratic hurdles. Once established, operations can run with relatively low risk of external disruption.

Export Compliance (Halal & Standards): As the country with the world’s largest Muslim population, Indonesia is inherently aligned with halal requirements. In fact, it has some of the strictest halal laws: the Halal Product Assurance Law mandates that a wide range of products (food, cosmetics, etc.) must be halal-certified by Indonesian authorities. Implementation has been phased, with mandatory halal certification deadlines (recently extended to 2026 for certain imported products). For an export-bound product made in Indonesia, getting halal certification would be essentially mandatory anyway – and the process is well-defined through the Halal Certification Agency (BPJPH and MUI, the Indonesian Ulema Council). So, Dubai Lolly’s manufacturing in Indonesia would automatically yield a halal-certified product (assuming ingredients are halal), recognized by other Muslim-majority markets. The halal compliance culture is ingrained: workers are accustomed to halal standards (segregation of any non-halal materials, etc.), though in this case, ingredients are largely fruits and dairy which are halal by nature (just ensure any gelatin or flavor alcohol is avoided). As for general export standards, Indonesia has improved but still catching up in certain areas. Quality control can vary by company. However, any factory aiming at export typically adopts international standards; many Indonesian food exporters are HACCP or ISO 22000 certified. The government and industry have pushed to meet global benchmarks, especially when entering markets like the EU or US. For instance, Indonesian seafood plants adhere to EU hygiene regs, and fruit exporters meet China’s and Australia’s stringent phytosanitary rules. So, the know-how is present to comply with international quality and safety standards. Another factor: Indonesia often requires halal even for export-bound goods (to maintain overall ecosystem integrity), which aligns perfectly with needs for the UAE. In summary, halal compliance in Indonesia is excellent (practically guaranteed), and export standard compliance, while needing diligence, is achievable given the country’s track record in various food categories.

Scalability: Indonesia’s sheer size gives it immense scalability. A venture could start small and, if demand increases, scale up within Indonesia almost indefinitely. The country has ample land for new factories (especially outside Jakarta, where the government encourages industries to spread), and an enormous labor pool to staff expanded operations. If Dubai Lolly’s needed to multiply production, Indonesia could facilitate that either by expanding the existing facility or opening additional ones in different regions (for example, one in Java, one in Sumatra, etc.). Because of its domestic market size, scaling production might also open opportunities to sell locally or regionally, adding stability to the business model. Infrastructure scaling would require ongoing improvements, but Indonesia is investing heavily in infrastructure as part of its development plans (new ports, new power plants, etc.). The government is also keen on export-oriented investment, so a successful food export factory could get support or at least prioritization (maybe easier freight or expansion permits). Skilled managerial talent might need development as you scale, but that can be mitigated by training and perhaps bringing in some foreign experts for oversight. One possible hurdle when scaling up in Indonesia is bureaucratic: larger operations may attract more regulatory scrutiny or complex compliance (e.g., environment permits if you use more water/energy). However, these are standard growth pains and manageable. On the whole, Indonesia provides virtually unlimited scalability – it could handle not just increased volumes for UAE but even if the brand grows across Asia and Europe. The combination of space, labor, and a government hungry for industrial growth means Indonesia can support massive scaling. The key is to ensure management systems keep pace with expansion to maintain quality, which is an internal challenge rather than an external limitation.

India (South India focus)

Fruit Access: India is an agricultural giant, especially for fruits. It is the world’s largest producer of mangoes – about 25-26 million tons annually (nearly half the world’s mangoes). South India, in particular, is home to famous mango varieties (Banganapalle, Totapuri, etc.), and states like Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu are major mango growers. Coconut is another strength: South India (Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka) has vast coconut plantations, making India the world’s third-largest coconut producer. Tropical fruits of all kinds flourish in India’s diverse climate – bananas (India is #1 globally), pineapples (grown in Northeast and South), papaya, guava, jackfruit (the south has plenty; jackfruit is even the national fruit of Bangladesh/Indonesia but also common in South India). For lychee, that is primarily grown in North India (Bihar, Uttar Pradesh) – not in the south – but given India’s internal trade, sourcing some from the North is feasible (cold-chain trains/trucks now move fresh litchis within India). Dragonfruit is a newer crop India has embraced: states including Karnataka, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, and Gujarat have begun cultivating dragonfruit (locally renamed Kamalam in some regions) under government programs. In fact, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka are among the top five dragonfruit producing states as of 2023, so South India is already growing the fruit needed for paletas. Passionfruit grows in India’s Northeastern states and parts of South India’s hill stations (Kodagu in Karnataka, Nilgiris in Tamil Nadu) – while not extremely common, it is available and could be contracted from those regions. Additionally, India offers spice fruits like tamarind or citrus like calamansi (from Northeast) that could inspire fusion flavors for the brand. The advantage in India is not just quantity but also variety and cultural affinity for fruit – e.g., there are scores of mango varieties to choose for different flavor profiles. The supply chain domestically can be arranged to bring needed fruits to the manufacturing site (though it requires coordination given the country’s size). In summary, India (including South India) can supply virtually every fruit needed either within the region or from other parts of India, supported by it being the top producer globally for many of them. The fruits are often available at relatively low cost, and quality can be excellent (Alphonso mango, for instance, is premium).

Labor: India’s labor is plentiful and low-cost, particularly in manufacturing sectors. While exact costs vary by state, South Indian states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka have higher minimum wages than, say, Bangladesh, they are still low by global standards (manufacturing wages often in the range of $150-250 per month for unskilled workers). Overall, India ranks #1 for cheapest manufacturing costs in some global indices. Moreover, the workforce has segments of high skill – especially in South India, education levels are relatively high, and there is a culture of engineering and technical training (for example, many food technology graduates come from institutions in Tamil Nadu). English proficiency is a significant plus in India; communication from management to shop-floor can be done in English or the regional language (but at least documentation and training materials can be in English). In terms of reliability and skill in food production, India has a mixed track record: on one hand, it has world-class pharmaceutical and dairy plants (e.g., Amul’s massive dairy factories, Nestlé’s food factories) run by Indian staff; on the other, smaller processing units sometimes struggle with consistency. But if one hires from the large talent pool (including food technologists and quality experts), an operation can be staffed to meet premium standards. Labor relations in South India are generally stable; there are unions, but the environment is industrialized and strikes in export industries are uncommon. The government’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes in food processing also encourage skill development. As Sphere Resources notes, India offers cost-effective manufacturing with a sizable talent pool, plus the advantage of English communication. One potential challenge is the work culture can be bureaucratic and hierarchical, which may need management attention to instill a quality-centric culture on the line. Overall, Indian labor is low-cost, with the added benefit of high education and English skills among supervisors, making it quite suitable for a brand that requires careful adherence to recipe and hygiene.

Infrastructure & Co-packing: India’s food processing infrastructure is extensive but can be uneven. In South India, there are modern food parks (e.g., Mega Food Park schemes in Andhra, Kerala, Karnataka) that provide common facilities like cold storage, IQF (Individual Quick Freezing) units, packaging centers, etc. India has a huge dairy cold-chain (for milk and ice cream distribution domestically), meaning refrigeration tech and suppliers are present. Major ice cream manufacturers like Hatsun and Arun (in Tamil Nadu) or Ibaco, Lazza, etc., operate in South India, so frozen dessert expertise exists locally. While co-packing in the Western sense (independent contract manufacturers) is not highly developed in India’s food sector (often companies produce in-house), it is growing. For instance, there are co-packers for snacks and beverages; for ice cream, some smaller brands outsource production to larger dairy firms occasionally. If not a pre-existing co-packer, one could likely partner with a big Indian ice cream or frozen food company to utilize spare capacity. Alternatively, setting up a dedicated facility in an agri-export zone could yield benefits like subsidies and tax breaks. Infrastructure like electricity and water is reliable in industrial zones, though costs can be high (power is somewhat expensive in India, but backup generators are common). Transportation within India improved with new highways, but moving goods can still face delays; however, being in South India means seaports like Chennai, Cochin, or Mumbai (via rail) can be accessed for export. India’s LPI infrastructure rank was 47 in 2023, reflecting significant improvement (ports and logistics digitalization). Specifically, India moved up to 38th overall in LPI 2023 and had notable improvements in port operation and timeliness, meaning the export infrastructure is becoming more efficient. Cold chain infrastructure is expanding fast in India due to government focus (they want to cut food wastage). For example, India’s cold storage capacity has grown to be one of the world’s largest, though largely used for domestic dairy and produce. In summary, India’s infrastructure can handle a high-end frozen dessert production, especially in a well-chosen location. It may not be plug-and-play like in Thailand, but with the country’s massive food industry, all necessary components (machinery, storage, skilled technicians) are available. Co-packing might require creative joint ventures or local partnerships, but the capability exists given India’s scale in ice cream (India has the world’s biggest ice cream consuming population after the US, so production volume is high).

Logistics & Proximity: India has a prime advantage in proximity to Dubai. South India (e.g., Kochi or Chennai ports) is about 3–5 days sailing to Dubai across the Arabian Sea and Gulf of Oman, and western Indian ports (Mumbai/Gujarat) even closer (~2–3 days). This short transit greatly reduces the risk for frozen shipments and costs. Additionally, there is heavy shipping traffic between India and UAE due to strong trade ties and Indian diaspora demand – meaning frequent vessel schedules. India’s LPI ranking improvement underscores its better international shipment and tracking systems. In fact, India is now ranked 22nd in the world for the international shipments sub-index (which measures ease of arranging competitively priced international shipments), reflecting how much easier it’s become to export from India. The logistics channels to the UAE are very well-established: the UAE is a top export destination for India’s agricultural and processed products. For example, Indian mangoes (Alphonso) are flown and shipped to Dubai every summer in large quantities, requiring cold-chain reliability. Similarly, meat and seafood exports to the Gulf have spurred specialized reefer supply chains. Cold storage and container handling at major ports (like Nhava Sheva/JNPT near Mumbai) are of international standard. If manufacturing in South India, one might ship out of Kochi or Chennai or Tuticorin; these have slightly smaller capacities than Mumbai, but Kochi in particular handles lots of food exports and is geographically closest to UAE. Air logistics are also excellent – there are numerous daily flights from South Indian cities (Cochin, Bangalore, Chennai) to Dubai and Abu Dhabi, useful for urgent shipments (and commonly used for perishable high-value exports like fresh seafood or specialty foods). One more angle: India and UAE have a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed in 2022, which reduces tariffs and eases trade procedures for many goods. This could benefit exports of food items by lowering duties and simplifying customs between the two nations. Customs clearance in India has also modernized (with single-window systems and risk-based inspections), reducing delays. Thus, India offers fast, cost-effective logistics to Dubai, arguably the best among all candidate countries due to closeness and trade volume. The main caution would be internal transport: getting products from a South Indian factory to the western seaport could involve a day or two by road/rail, but those links are improving (for example, a reefer train service from Chennai to Mumbai exists). Overall, on logistics, India (especially if leveraged via its west coast ports) can deliver speed and reliability for cold-chain exports to the UAE.

Stability & Business Climate: India is a stable democracy and a fast-growing economy. Political power can change via elections, but core economic policies have largely converged on promoting growth, manufacturing (Make in India), and ease of doing business. While India is vast and governance quality varies by state, South Indian states are generally well-governed, with Tamil Nadu and Karnataka often considered investor-friendly. There are no serious internal conflicts in those states (they are peaceful, barring occasional protests/strikes which are typically limited in duration). The macroeconomy is robust – even with global turbulence, India’s GDP growth is strong (~6-7% annually), providing a conducive environment for business expansion. For foreign investors, India historically had bureaucracy and regulatory complexity as the main issues. However, reforms have been simplifying things (e.g., scrapping retrospective taxes, improving bankruptcy laws). Starting a business still involves paperwork, but once established, operations are not usually under threat. Policy consistency and contract enforcement have improved (though not yet at Singaporean levels). Another aspect: corruption at lower levels can occur, but in export-oriented sectors located in special zones, this is mitigated by digital systems and centralized administration. The government offers incentives for food processing and has set up a dedicated ministry for Food Processing Industries, showing prioritization of the sector. One must note that compared to a tightly controlled state like Vietnam, India’s democratic nature means sometimes sudden regulatory changes or activism (like a ban on plastic straws that affected dairy product packaging in 2022) – companies need to adapt, but those incidents are exceptions. On the positive side, India has a huge domestic market which provides optionality; if global demand dips, one can pivot to Indian consumers (who are developing a taste for exotic desserts), giving flexibility not present in smaller countries. As for legal protections, India has a strong judiciary (though slow), and intellectual property laws exist (enforcement is improving). Summarily, India offers a stable and improving business climate, though navigating its bureaucracy requires patience and good local advisors. It doesn’t have the near-total policy stability of a one-party state, but it makes up with the rule of law and huge market opportunities that align with a strategic business plan.