What Entrepreneurship Actually Taught Me

I didn’t grow up knowing what I wanted to be.

At school, I felt out of place more often than not. I wasn’t particularly academic, I didn’t see the point of most subjects, and I couldn’t understand how any of it translated into a real job — partly because no one ever explained what jobs actually existed. The world of work felt abstract, distant, and oddly secretive.

I went to the same boarding school as Richard Branson — Stowe — which sounds impressive until you realise that prestige doesn’t magically make you feel like you belong. I took mostly science subjects and was often the only girl in the room. I was creative, shy, and quietly observant. I didn’t put my hand up. I avoided attention. I was far more afraid of humiliation than failure.

Earlier, at my prep school, Thomas’s, things were different. School was creative. We did theatre, sport, art. Being “well-rounded” mattered more than being perfect. Boys and girls were friends. I was always in detention — but I loved it there.

Then came adolescence, boarding school, and the sudden, uncomfortable shift that happens when girls become something to be rated rather than befriended. That experience — of being observed, judged, objectified — stayed with me far longer than any exam result.

I didn’t flourish academically. I was lost. And I had no clear career path.

The book that changed everything

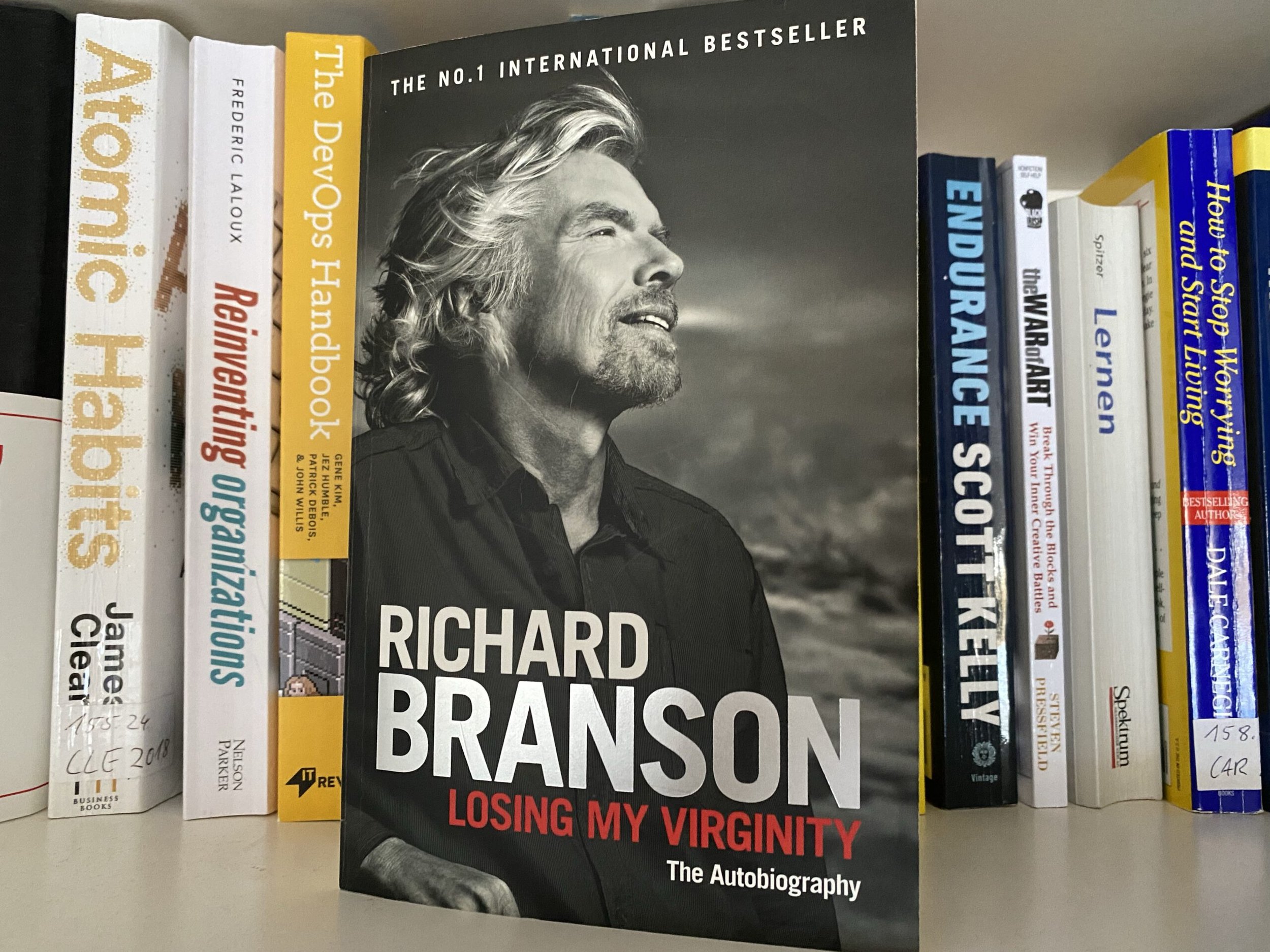

One afternoon in the school library, I picked up Richard Branson’s autobiography.

For the first time, I recognised myself in someone else’s story. Dyslexic. Creative. Sporty, but derailed by injury. Someone who didn’t fit the traditional mould and hadn’t thrived in the classroom — yet still built something meaningful.

It gave me hope.

Around the same time, on a school trip called Outward Bound, a former military instructor drew a dot in the dirt and a circle around it.

“This,” he said, “is your comfort zone. Everything outside it feels frightening. But every time you step beyond it, the circle grows.”

That idea became my mantra.

I started putting my hand up. I joined debating. I joined societies I wasn’t good at. I spoke French aloud in class — something I’d always known I could do, but had been too scared to demonstrate. My life didn’t suddenly become easy, but it became active. I felt like I was moving, rather than waiting.

Dropping out — and finding my people

I went to university. Then I dropped out.

Shortly afterwards, London entered a tech boom. Startup meetups were everywhere. There was optimism in the air — the sense that technology could level the playing field, that ideas mattered more than pedigree, that you didn’t need permission to build.

I found my tribe.

This was the era of Facebook, of the Social Network movie, of glamorised dropouts and hoodie-wearing founders. Silicon Valley culture flooded into London: if you had an idea, grit, and originality, you could build something — maybe even become a unicorn. Background didn’t matter. Class didn’t matter. Failure wasn’t shameful; it was proof you’d tried.

I absorbed that mentality completely.

I joined a startup building a social network. I followed Y Combinator. I internalised the idea that within five years, if you hustled hard enough, you could change your life entirely. It felt radically anti-establishment — almost the opposite of the British class system I’d grown up around.

For a long time, I thrived in that world.

What they don’t tell you about building companies in the UK

Over the years, I set up multiple businesses in the UK.

Here’s the part people don’t talk about enough: it is very easy to start a company here — and surprisingly punishing to stop one.

I learned how to incorporate quickly. What I didn’t learn — and no one warned me — was how hard it is to:

Hire people responsibly

Understand tax before it’s a problem

Wind down a business cleanly

Carry the reputational shadow of closed companies

In the UK, a trail of shut-down companies doesn’t read as “entrepreneurial learning”. It reads as instability. Recklessness. Failure.

In the US, that same history would barely raise an eyebrow.

I also realised how naïve many founders are at the start — myself included. I thought setting up a company was like buying a domain name. In reality, you can (and should) test ideas long before incorporating. But the system doesn’t guide you to do that. It lets you make the mistake, then quietly records it forever.

At the same time, the moment you try to grow — to employ people — the administrative weight increases dramatically. Taxes, payroll, compliance, legal risk. I’ve shut down companies not because the ideas were bad, but because the overhead became overwhelming too early.

That isn’t a personal failure. It’s a structural one.

Growing older — and more responsible

In my thirties, after spending time in the US and working deeply in AI and technology, my views became more nuanced.

I’ve seen how technology can empower people — and how it can be weaponised. I’ve seen what happens when innovation is driven purely by profit, without responsibility to society. I no longer believe that “move fast and break things” is a sufficient philosophy.

But I am still pro-business. Pro-individual creativity. Pro-people making the most of their lives.

That combination probably makes me quite conservative in temperament — but not dogmatic. I believe in enterprise with guardrails. Freedom with responsibility.

What I want to change

I want the UK to be a place where:

Creative, idealistic founders can experiment safely

Closing a business responsibly doesn’t haunt you forever

People learn how to hire, tax, and scale before they’re punished for not knowing

AI and software reduce administrative burden instead of increasing anxiety

Co-founders can find each other and road-test ideas without lifelong consequences

Entrepreneurship shouldn’t be reserved for the cynical, the already-wealthy, or the legally fluent. It should be accessible to people like I was: curious, shy, creative, idealistic — willing to take risks, but not reckless.

Stepping outside the circle — again

That circle in the dirt never really goes away.

Even now, writing this, I’m stepping outside it again. Talking honestly about failure, confusion, and systemic flaws isn’t comfortable. But comfort has never been where growth happens.

I didn’t become who I am because everything went right. I became who I am because I kept stepping beyond the edge of what felt safe — learning, adjusting, and trying again.

If we want more entrepreneurs in the UK — not just more companies — we need to build systems that recognise that truth.