The UK Built DeepMind. Google Owns It. Labour Is About to Make the Same Mistake Again.

In 2014, Britain watched one of its most strategically important technology companies get sold to an American tech giant for £400 million. DeepMind, founded in London just four years earlier, had assembled some of the world's leading AI researchers and pioneered breakthrough work in deep reinforcement learning. The acquisition by Google seemed like a commercial success story at the time—British innovation validated by Silicon Valley money.

Ten years later, we can see it for what it really was: one of the most catastrophic strategic failures in British technological history. DeepMind went on to develop AlphaGo, AlphaFold (solving the protein folding problem), and numerous other AI breakthroughs that will shape the 21st century. All of it now sits under American corporate ownership. The intellectual property resides in California. The strategic control belongs to Alphabet. The data infrastructure integrates with Google's ecosystem. And Britain has precisely zero meaningful influence over how these capabilities are deployed.

The real tragedy isn't that this happened. It's that Labour is about to do it all over again.

The £500 Million Illusion

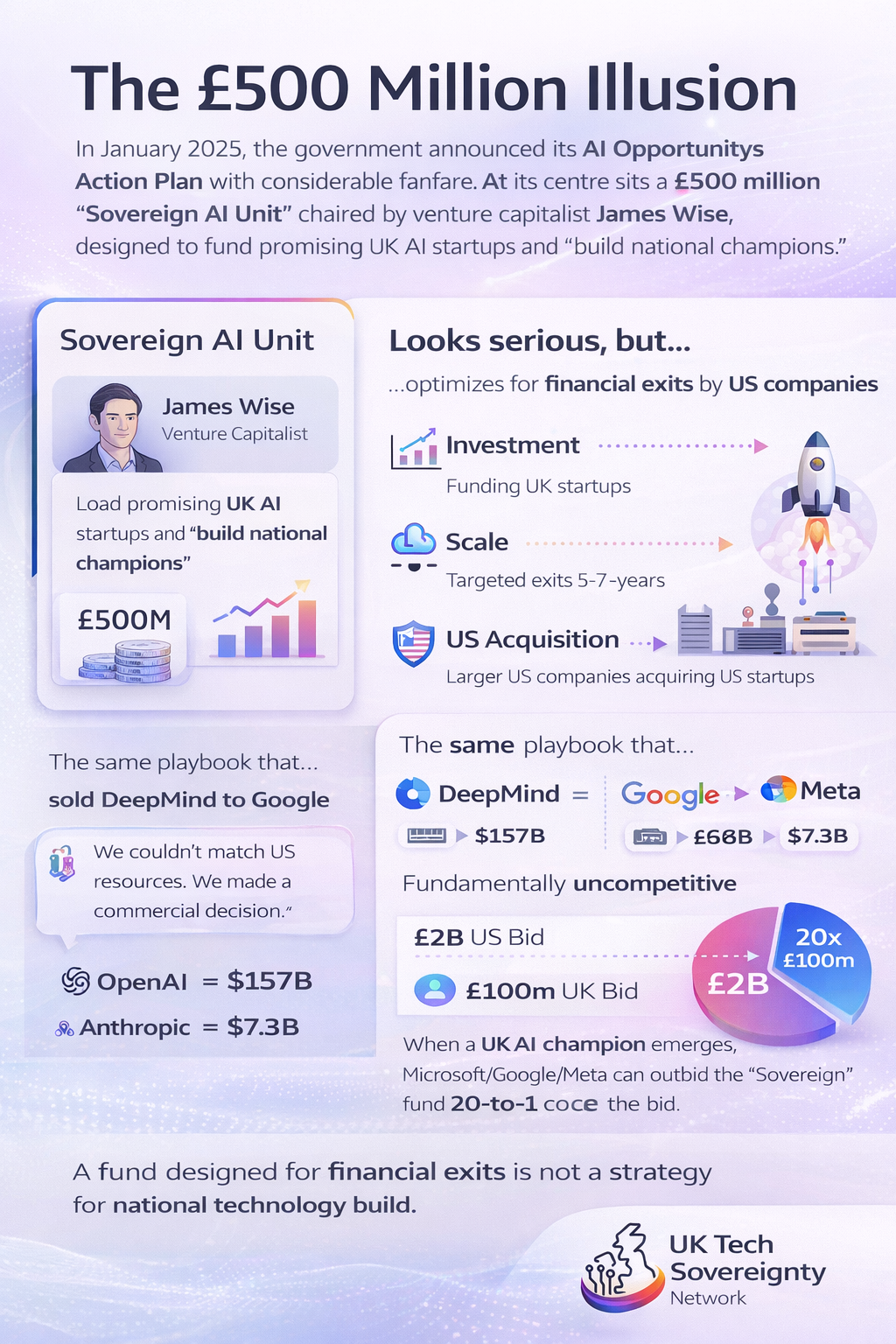

In January 2025, the government announced its AI Opportunities Action Plan with considerable fanfare. At its center sits a £500 million "Sovereign AI Unit" chaired by venture capitalist James Wise, designed to fund promising UK AI startups and "build national champions." The language sounds appropriately strategic. The intention appears serious. But the structure guarantees failure.

Here's why: James Wise is a partner at Balderton Capital, a venture capital firm. His expertise is in identifying promising companies, providing growth capital, and generating returns for investors through exits—either acquisition by larger companies or public market listings. The Sovereign AI Unit is explicitly designed to "make a meaningful return for the British taxpayer," which means it's optimizing for financial outcomes on VC timelines: 5-7 year exit horizons.

This is precisely the logic that sold DeepMind to Google. When DeepMind's founders accepted Google's £400 million offer in 2014, they were making a rational commercial decision. Google could offer compute resources, talent compensation, and strategic resources that no UK entity could match. The British government wasn't an alternative buyer—it barely understood AI as a strategic issue, let alone had mechanisms to provide patient capital or governance protection.

A decade later, with £500 million instead of £0, we've made marginal progress. But the fundamental problem remains: £500 million cannot compete with American hyperscaler economics. OpenAI is valued at $157 billion. Anthropic has raised $7.3 billion. When the next DeepMind emerges—when a brilliant UK AI company demonstrates breakthrough capabilities—Microsoft or Google or Meta will simply offer £2 billion and our "sovereign" fund will be outbid twenty-to-one.

The Sovereign AI Unit will produce exactly what VC-structured funds always produce: successful companies that get acquired. We'll celebrate the "thriving ecosystem," generate excellent financial returns, and watch strategic capabilities transfer to American ownership. Then in 2035 we'll commission another report about how "Britain is great at invention but poor at commercialization" and wonder why we keep losing our most important companies.

What Sovereignty Actually Requires

The DeepMind acquisition wasn't inevitable. Multiple governance mechanisms could have prevented it, mechanisms that exist in other countries and have historical precedent in Britain itself. The failure wasn't technological or commercial—it was institutional. We lacked the structures to protect strategic capabilities from acquisition.

Consider what Germany did with Volkswagen. Under the "Volkswagen Law," the German government retains special voting rights that allow it to veto major strategic decisions, including foreign acquisition attempts. This doesn't prevent commercial operation or private ownership—VW is a publicly traded company. But it ensures that critical strategic decisions require government consent. When Porsche attempted a hostile takeover in 2008, the government could block it. Germany maintains strategic control without preventing normal commercial activity.

Or look at what Singapore does through Temasek, its sovereign wealth fund. Temasek takes long-term equity positions in strategic companies, measuring success by capability development over 30-50 year horizons rather than quarterly returns. It provides patient capital that allows companies to build capabilities without exit pressure, and retains governance rights that prevent acquisition without state approval. Singapore's approach has built genuine strategic autonomy in critical technologies despite being a small nation.

Britain could have required that any AI company receiving public research funding—whether through UKRI grants, university partnerships, or public compute access—grant the government a "golden share" with veto rights over foreign acquisition. This wouldn't prevent companies from raising private capital or achieving commercial success. It would simply ensure that when Google came offering £400 million, the government could say: "We recognize DeepMind's commercial value, but we're designating this as strategic national capability. If you want to sell, find a British buyer or structure a partnership that maintains UK control."

We could have established a genuine patient capital fund—£10-20 billion over five years, structured like Germany's KfW development bank—that provides growth capital without expecting exits. Companies could access computational resources, talent retention funding, and strategic investment on condition that they maintain UK headquarters and grant the government meaningful governance rights. This wouldn't prevent eventual acquisition, but it would dramatically reduce the pressure that forces founders to sell.

We could have reformed university IP rules to require that publicly-funded research comes with "march-in rights"—if a university spinout company is acquired by a foreign entity within ten years of receiving public research funding, 20% of the acquisition value returns to public coffers and the government retains licensing rights for strategic applications. This creates friction in acquisition discussions while ensuring the public benefits financially when private companies monetize publicly-funded research.

None of this happened. DeepMind was founded in 2010. It received no special designation as strategically important. When it accepted Google's offer in 2014, the government had no mechanism to intervene. The National Security and Investment Act—which gives the government power to review and block acquisitions on national security grounds—didn't pass until 2021, seven years too late.

Why the NHS-DeepMind Partnership Reveals the Problem

The consequences of this failure became clear through DeepMind's subsequent work with the NHS. In 2016, DeepMind partnered with the Royal Free Hospital to develop systems for detecting acute kidney injury. Then came work on eye disease detection at Moorfields. Then COVID-19 response systems. Then broader health data infrastructure.

These partnerships involved NHS data—patient records, diagnostic images, treatment outcomes—being processed through DeepMind's systems. DeepMind claimed these relationships would advance medical AI while protecting patient privacy. The work produced genuine clinical value. But it also created a troubling dynamic: British public health data feeding American corporate AI development, with ultimate control residing in California.

When concerns were raised about data governance, DeepMind pointed to contractual protections and privacy safeguards. These were real but insufficient. The problem isn't that DeepMind violated agreements—it's that the fundamental power relationship had reversed. The NHS needed DeepMind's AI capabilities for modern healthcare delivery. DeepMind needed NHS data for AI development. But DeepMind was now part of Google, accountable to American shareholders and subject to US government jurisdiction. If the US intelligence community asked for access to health AI systems, could DeepMind refuse? If Google decided to restructure DeepMind in ways that conflicted with NHS interests, what recourse existed?

In 2021, DeepMind's health division was absorbed directly into Google Health. The assurances about independent operation and UK governance disappeared into normal corporate integration. This wasn't a betrayal—it was the predictable outcome of selling strategic capability to a foreign corporation. Of course Google integrated DeepMind. Of course the AI capabilities developed partly through NHS partnerships became Google assets. That's what happens when you don't maintain sovereign control.

The parallel to Palantir is striking. Palantir entered the NHS during COVID-19 offering emergency data infrastructure for £1, then systematically built dependencies until the NHS became unable to function without Palantir systems. By 2024, the NHS had committed £330 million to Palantir without competitive procurement, justified entirely by previous dependence. The difference is that Palantir was always explicitly American, always obviously a US intelligence-linked entity. DeepMind was British. We built it. We funded the research behind it. We trained the talent who made it work. Then we sold it, and acted surprised when it started serving American strategic interests.

What Labour Should Do Instead

The current government approach—£500 million in VC-style funding, "AI Growth Zones" with £5 million each, £100 million for government to act as "first customer"—represents marginal improvement on previous policy. But it operates within the same failed logic that lost DeepMind: commercial frameworks for strategic problems.

Real sovereignty requires institutional architecture designed for irreversibility. Here's what that looks like:

First, establish mandatory golden share requirements. Any AI company receiving more than £1 million in public funding—including research grants, compute subsidies, procurement contracts—must grant the government a golden share with veto rights over foreign acquisition above 25% ownership, relocation of headquarters outside the UK, or major changes to data residency. This doesn't prevent commercial operation but ensures strategic capabilities can't be sold without explicit government consent.

Second, create genuine patient capital. A £10-20 billion AI National Development Bank, structured like Germany's KfW, would provide growth capital on 30-50 year timelines without expecting exits. Success would be measured by strategic capability development, not financial returns. Companies could access resources without acquisition pressure, knowing patient capital enables long-term development rather than forcing near-term exit.

Third, reform university IP retention. Require that universities receiving public research funding maintain government "march-in rights" for strategically important discoveries. If a university spinout is acquired by a foreign entity within ten years of receiving public funding, 20% of acquisition value returns to public coffers and the government retains licensing rights. This ensures public benefit from publicly-funded research.

Fourth, expand the National Security and Investment Act. Currently focused on narrow national security criteria, it should explicitly include "technological sovereignty" as grounds for intervention. All AI companies above £50 million valuation should face automatic review before foreign acquisition. The government should have power to designate specific companies as "strategic AI capabilities" that cannot be acquired by foreign entities without parliamentary approval.

Fifth, aggregate municipal procurement. Instead of scattered city-level AI contracts, coordinate 20-30 major cities to commit £500 million-£1 billion annual procurement budget to UK-developed AI systems. Offer 10-year contracts with built-in scaling, creating predictable revenue that reduces exit pressure on domestic companies. This uses public sector buying power to create strategic capabilities while ensuring democratic oversight.

Finally, establish constitutional protection for critical AI capabilities. Create an independent AI institution with governance modeled on the BBC—funded through hypothecated taxation (e.g., 2% levy on cloud computing services), protected by parliamentary charter, governed by cross-party oversight, with explicit prohibition on acquisition without two-thirds parliamentary vote. This creates genuinely sovereign capability that cannot be sold regardless of commercial pressure.

None of this is radical in the sense of being unprecedented. Germany does it with Volkswagen Law. Singapore does it with Temasek. France does it with strategic sector protections. Even the United States does it through CFIUS (Committee on Foreign Investment) and Defense Production Act authorities. Britain simply needs to apply to technology companies the protections we once applied to defense contractors and critical infrastructure.

The DeepMind Test

Every proposed AI policy should be evaluated against a simple standard: Would this have prevented Google from acquiring DeepMind?

Labour's current approach fails this test completely. The £500 million Sovereign AI Unit couldn't outbid Google's £400 million offer, much less the £2-5 billion that a strategic AI company would command today. The AI Growth Zones provide infrastructure but no acquisition protection. The "first customer" commitment offers procurement revenue but doesn't prevent sale. None of it creates irreversible sovereign control.

The proper sovereignty framework passes the test easily. Golden share requirements mean DeepMind founders couldn't sell without government consent. Patient capital reduces acquisition pressure by providing alternative funding. Municipal procurement aggregation creates strategic revenue without dependence on commercial exits. Constitutional protection makes critical capabilities non-sellable by design.

This matters because the next DeepMind is being founded right now. Brilliant researchers, world-class universities, breakthrough discoveries—Britain still has these advantages. But without institutional structures to protect strategic capabilities, we'll watch the next generation of critical AI companies follow DeepMind's path: British invention, American ownership, strategic subordination.

The Boring Work of Sovereignty

The hardest thing about building genuine technological sovereignty isn't the policy design—it's sustaining boring work across electoral cycles. Golden share requirements need legislation that survives government changes. Patient capital funds need multi-year appropriations that resist short-term cuts. University IP reforms need administrative follow-through across hundreds of institutions. Constitutional protections need cross-party consensus that transcends partisan competition.

None of this generates immediate political credit. Ministers who champion 10-year sovereign capability programs won't be in office when programs succeed. Civil servants who build institutional infrastructure won't receive recognition when infrastructure proves essential. Citizens who demand sovereignty won't see immediate benefits justifying political support.

But competence delivers what rhetoric cannot. Germany built manufacturing sovereignty through decades of patient industrial policy. Singapore built technological capability through sustained investment in strategic sectors. Even the United States—despite free market ideology—maintains technological sovereignty through decades of Defense Department funding, DARPA innovation programs, and aggressive use of national security authorities to protect critical capabilities.

Britain has the resources. We have the expertise. We have potential partners across Europe and Africa who share interest in democratic alternatives to US-China technological duopoly. What we lack is political will to sustain boring systematic work until it's completed.

The choice is immediate. Not distant future hypothetical but decisions available tomorrow: Draft golden share legislation. Capitalize the development bank. Reform university IP rules. Expand NSI Act authorities. Coordinate municipal procurement. Establish constitutional protections.

Do this systematically over five years, and Britain maintains strategic autonomy in critical technologies. Don't do it, and accept comfortable subordination dressed as pragmatic partnership.

We built DeepMind. We lost it. We know exactly why we lost it. We know exactly what policies would prevent losing the next one. The question isn't whether we understand the problem. It's whether we have the discipline to do the boring work of solving it.

Labour keeps saying it wants to make Britain an "AI superpower." Superb. Start by ensuring the next DeepMind can't be bought by Google without your permission. Everything else is commentary.

See content credentials

Join the GLOBAL TECH Sovereignty ALLIANCE

A professional forum for founders, technologists, policymakers, investors, and researchers focused on strengthening the UK’s technological sovereignty.

We discuss domestic capability in AI, semiconductors, cloud, data infrastructure, defence tech, and critical digital supply chains—balancing innovation, national resilience, and global collaboration.